Students with Hearing Impairment: Indicators of Vision Issues

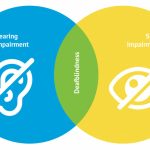

To support students and their families effectively, it is crucial to understand the students’ needs and abilities thoroughly. Students with hearing impairments—ranging from partial hearing to profound deafness—may sometimes exhibit behaviors that are ‘atypical’ and warrant further observation to detect potential vision impairments. Vision impairment encompasses a spectrum from blindness or very low vision to the inability to distinguish specific colors.

Vision impairment refers to eyesight that does not meet standard levels of correction.

Firstly, accessing the family history of students can be invaluable, as genetic factors often contribute to vision impairment. For instance, conditions such as Usher Syndrome or Waardenburg Syndrome Type II may be inherited. If two siblings are deaf or hard of hearing and one is diagnosed with Usher Syndrome or retinitis, the other sibling might also carry the same genetic predisposition. Additionally, the family’s place of origin can be relevant, as certain regions have a higher incidence of syndromes like Usher.

Reassessing a student’s vision should be considered when physical signs such as regular rubbing, squinting, tearing of the eyes, excessive blinking, or frequent headaches are observed. Difficulty with glare may also manifest as a preference for wearing sunglasses and hats. Accidents or severe illnesses that affect vision include meningitis or prolonged high fever, significant traumatic brain injuries, autoimmune conditions, strokes, ototoxic complications, and chemotherapy.

Culture significantly influences students’ behavior. The deaf and hard of hearing community primarily uses visual sign language, making vision and eye contact crucial. In sign language, intentional eye contact and breaks are important; if a student has vision issues, they may use their vision differently. For example, they might view their communication partner from an angle rather than head-on, which could indicate a vision issue. Moreover, in signed conversations, there is a typical comfort distance of about six feet. If a student uses a different distance or responds differently depending on the distance, it may signal vision problems.

During signed conversations, specific behaviors can suggest vision impairment. For example, a student who frequently asks for signs to be repeated may have trouble following the speed of the signs or could be distracted by the lighting. In conversations involving multiple people, a student with peripheral vision loss may struggle to keep up, needing more head movement to follow the conversation and consequently appearing slightly off-topic. Additionally, a student who has difficulty visually following a conversation might appear indifferent, inattentive, or overly someone who monopolizes the conversation.

In the classroom, unusual ways of perceiving educational material can also indicate vision issues. A student might bring paper very close to their face, view their phone at an angle, close one eye, tilt their head, or frequently adjust their glasses to see better. A student with a limited visual field might choose to sit at the back of the class for a broader perspective or sit close to the teacher and board. Unusual reactions to lighting—such as discomfort with the smart board or various classroom lights—can also be a sign of vision problems.

Vision loss can result from eye injury, atypical eye shape, or complications in the brain.

Vision impairment may also affect the student’s movement. They may show poor hand-eye coordination, consistently trail desks or brush against walls for spatial orientation, appear clumsy, hesitant while walking, look down frequently, shuffle their feet, or adopt a wider stance for stability. Busy environments like crowded cafeterias or yards can be challenging for students with vision impairments, so it’s useful to observe their navigation skills in such settings.

Other indicators of vision issues include bumping into people or objects (such as trash cans, which require our lower vision field, are often dark and blend into the background), difficulty identifying faces, colors, or objects, and trouble locating personal items even in familiar environments. A high startle response can also be a sign, as deaf and hard of hearing individuals typically rely on vision for environmental awareness. If a student does not perceive someone approaching through peripheral vision, they may startle because they did not detect the person’s presence early enough.

Observation is an essential tool for gathering information about students and identifying their needs. Although many eye conditions present similar functional implications, knowing the specific diagnosis can help educational professionals create an optimal long-term plan. It is important to remember that the indicators listed above suggest possible visual needs but do not guarantee them.